What was once seen as nothing more than a procedural part of the elections process has, in the past two election cycles, evolved into something of a battlefield in the election denial movement.

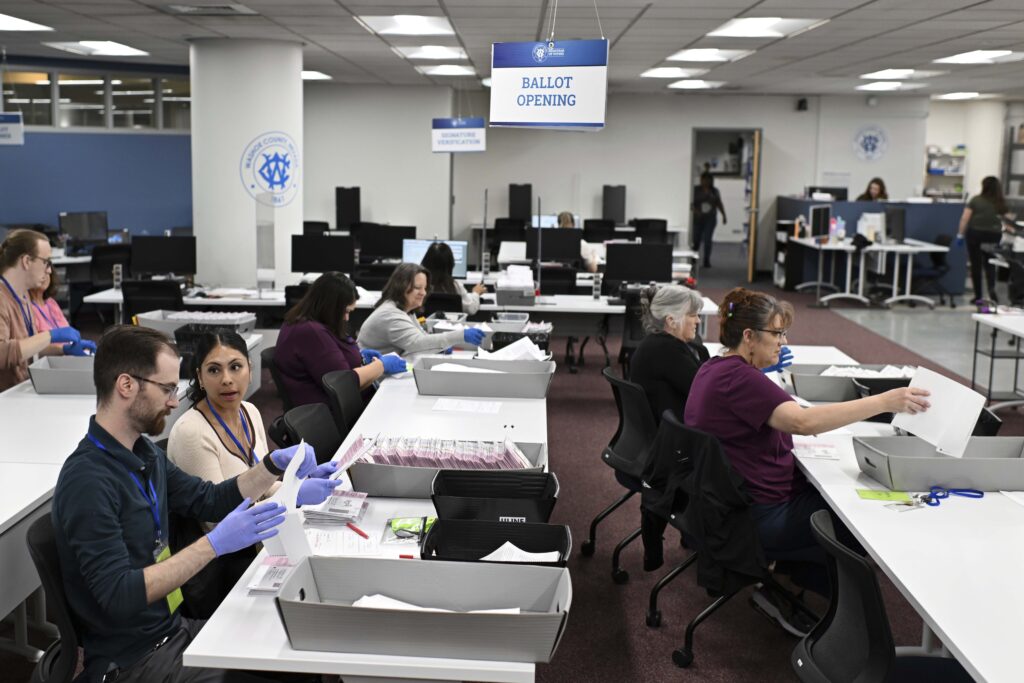

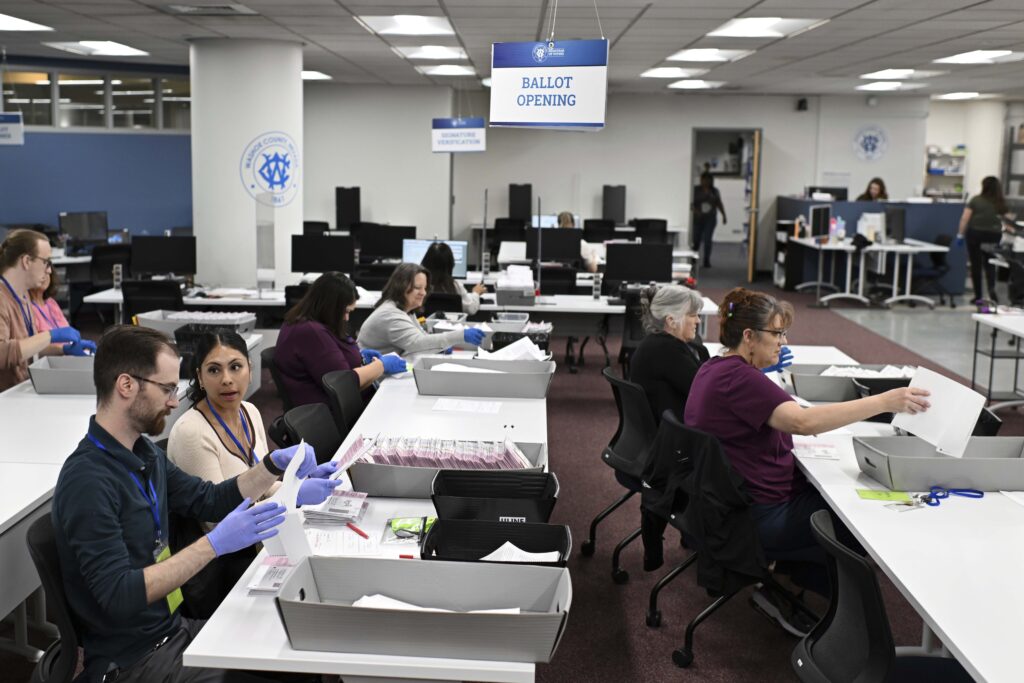

By all accounts, election certification is somewhat of a mundane statutory task: after tabulating all ballots — in-person, mail-in, provisional, absentee — local election officials certify that the ballot count is complete and accurate. That process is then repeated by election officials on the state level and, in the case of a presidential election, in Congress.

In 2022, nearly a dozen counties refused to certify the election results, prompting lawsuits and court orders.

Want to know more about the right-wing legal strategy leading up the election? Sign up for Matt’s newsletter Eye On The Right and get the latest updates sent straight to your inbox.

But given how former President Donald Trump and his sycophants have promoted election conspiracy theories in the past four years, election certification has become one of the more pervasive, and legitimate, concerns of the upcoming election. What happens when rogue county and local election officials who refuse to certify their jurisdiction’s election results? A recent Rolling Stone investigation found there are at least 70 election officials in key swing states with a history of promoting conspiracy theories related to the 2020 election — igniting concerns that such officials would refuse to certify the election results in their jurisdiction should they not be happy with whichever candidate wins.

Simply put, election certification is the process by which election officials basically affirm that the tabulation and canvassing of an election is complete and that the results are accurate. As the U.S Election Assistance Commission explains, after the canvassing process, election officials will certify the election results through different methods: through a local board, a chief election official or through canvassing boards. Lauren Miller Karalunas, a counsel for the Brennan Center for Justice, explained “certification is the process by which local election officials sign off on the completion of the election results to say that: yes, the many processes to tabulate the results and confirm that they’re correct, have all taken place.” While that process is a necessary step in the election process, it’s more “a formality that’s procedurally important, but substantively very narrow,” Karalunas told Democracy Docket.

Each state has specific statutes that outline a process to follow if a local official won’t certify an election.

Some states use a single official, like the secretary of state, to certify all the election results from that state. Whatever the method, states do this within 30 days after the election, though some do it within one day. This certification process, Karalunas stressed, is a “mandatory process for election officials to do. It is not the time for them to investigate election results. And that’s because there are other procedures like election contests and court proceedings that are specifically designed to answer legal questions about election results.”

As we saw in the 2020 election and the 2022 midterms, rogue election officials delaying, or outright refusing, to certify an election is something that happens now. It’s occurred in Arizona, Georgia, New Mexico, Pennsylvania and other states in recent years. The short answer is: there’s mechanisms in place to ensure elections are certified. As Karalunas noted, some states have specific statutes that outline a process to follow if a local official won’t certify an election. “So in Michigan, for example, the state law allows state election officials to take over certification at the local level if a local official refuses to certify,” she explained. In other states, the courts can step in, at the request of a voter, candidate, or another state official. The process, known as a writ of mandamus, involves a court to step in to legally compel a government official — in this case, an election official — to fulfill their duties, like certifying an election. But what happens when an election official refuses to comply with a court order to certify an election? They could be removed from their position. In the 2022 midterm elections in North Carolina, two officials were removed for refusing to certify. In such cases, Karalunas emphasized, safeguards are in place. “So in the last election cycle they removed two officials that refused to certify the election,” she said. “And then there are some additional federal and state rules that allow another person to just come in and actually fulfill that legal process.”

Yes and no. As the Rolling Stone article noted, and as Marc Elias explained in his latest column, “we are going to see mass refusals to certify the elections” because the GOP is “counting on the fact that if they don’t certify in several small counties, you cannot certify these statewide results.” Such refusals to certify local elections by rogue election officials are certainly going to cause a headache, but the important thing is that there are processes to ensure each election is properly certified. “Voters should be rest assured that if they see an attempt to refuse to certify an election in their jurisdiction, that does not mean that there was a problem with the elections,” Karalunas said. “There are processes in place to make sure that certification ultimately will happen in a timely fashion and that their vote will be counted.”

This post was updated to reflect that the two North Carolina officials were removed for refusing to certify an election, as well as to clarify that only some states have specific statutes that outline a process to follow if a local official won’t certify an election.

AFPI is hardly the first right-wing think-tank to get involved in election litigation but their recent pivot to election litigation is part of a larger right-wing focus on rolling back voting rights and sowing discord in elections through the courts.