We examined the injustices of prison labor nationwide — and lay the foundation for a more equitable path forward.

Share This Page June 15, 2022We examined the injustices of prison labor nationwide — and lay the foundation for a more equitable path forward.

Our nation incarcerates more than 1.2 million people in state and federal prisons, and two out of three of these incarcerated people are also workers. In most instances, the jobs these nearly 800,000 incarcerated workers have look similar to those of millions of people working on the outside. But there are two crucial differences: Incarcerated workers are under the complete control of their employers, and they have been stripped of even the most minimal protections against labor exploitation and abuse.

A new ACLU report, Captive Labor: Exploitation of Incarcerated Workers, explores the use of prison labor nationwide. Here’s what we found:

From the moment they enter the prison gates, incarcerated people lose the right to refuse to work. This is because the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects against slavery and involuntary servitude, explicitly excludes from its reach those held in confinement due to a criminal conviction. The roots of modern prison labor can be found in the ratification of this exception clause at the end of the Civil War, which disproportionately encouraged the criminalization and effective re-enslavement of Black people during the Jim Crow era, with impacts that persist to this day.

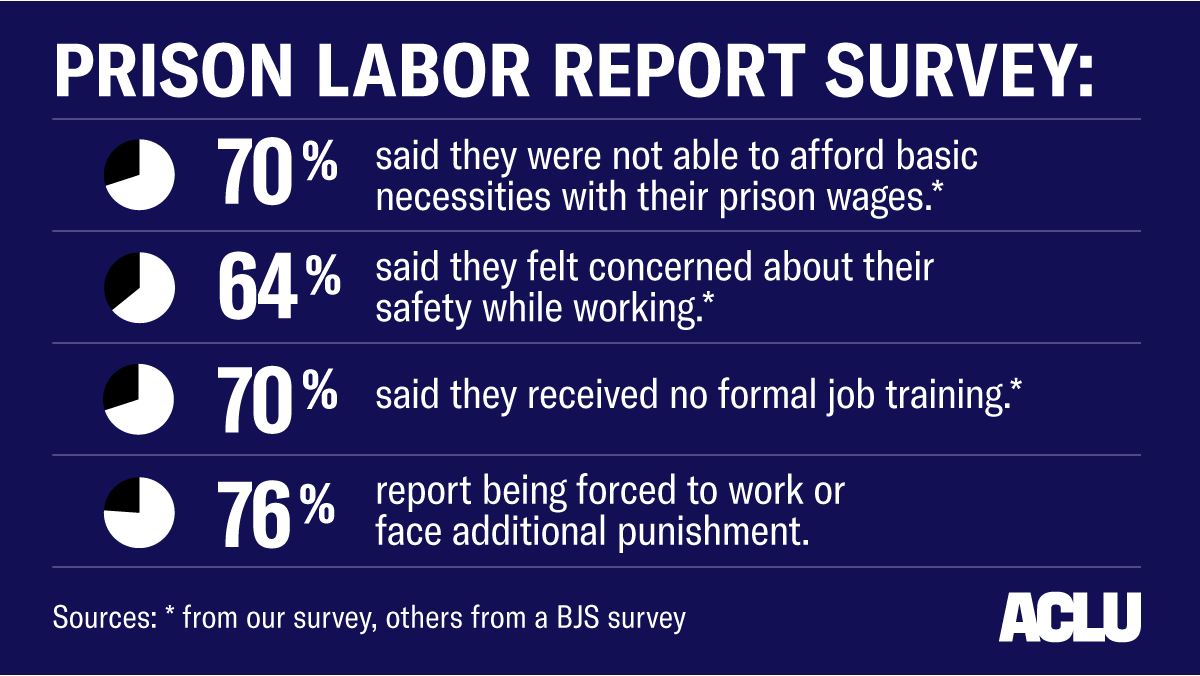

Today, more than 76 percent of incarcerated workers surveyed by the Bureau of Justice Statistics say that they are required to work or face additional punishment such as solitary confinement, denial of opportunities to reduce their sentence, and loss of family visitation. They have no right to choose what type of work they do and are subject to arbitrary, discriminatory, and punitive decisions by the prison administrators who select their work assignments.

U.S. law also explicitly excludes incarcerated workers from the most universally recognized workplace protections. Incarcerated workers are not covered by minimum wage laws or overtime protection, are not afforded the right to unionize, and are denied workplace safety guarantees.

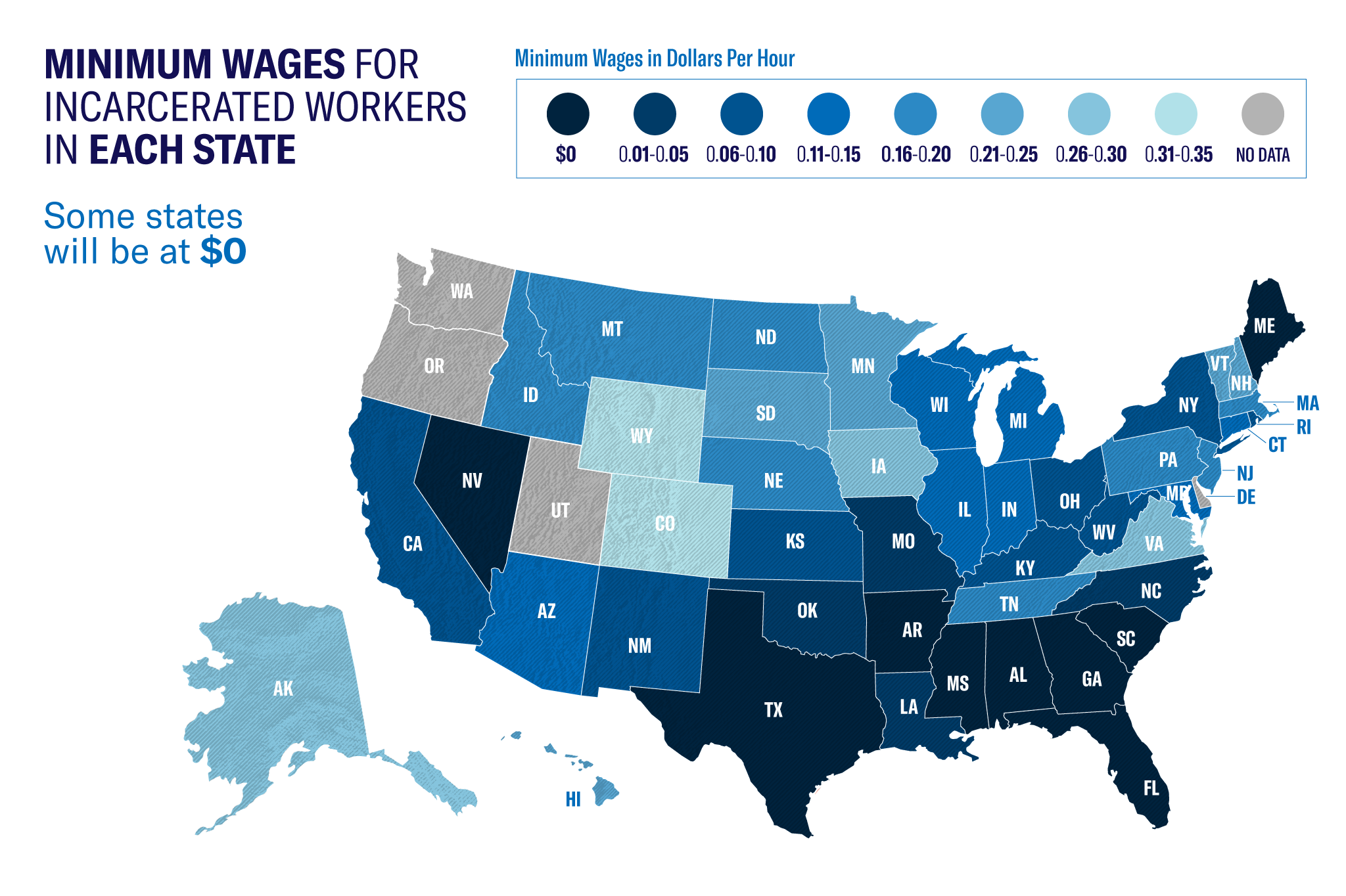

Incarcerated workers typically earn little to no pay at all, with many making just pennies an hour. They earn, on average, between 13 cents and 52 cents per hour nationwide. Wages remain stagnant for years, even decades. In seven states, incarcerated workers are not paid at all for the vast majority of work assignments.

Yet even these abysmal wages are not theirs to keep. The government takes up to 80 percent of these wages for “room and board,” court costs, restitution, and other fees like building and sustaining prisons. These wage deductions generally leave incarcerated workers with less than half of their gross pay. Workers are left with even less disposable income because prison systems charge incarcerated people exorbitant costs for basic necessities, like phone calls to loved ones, hygiene products, and medical care. Almost 70 percent of surveyed incarcerated workers said they were not able to afford basic necessities with their prison wages.

Because incarcerated workers’ wages are so low, families already struggling from the loss of income when a family member is incarcerated must step in to financially support an incarcerated loved one. Families with an incarcerated loved one spend $2.9 billion a year on commissary accounts and phone calls, and more than half of these families are forced to go into debt to afford these costs.

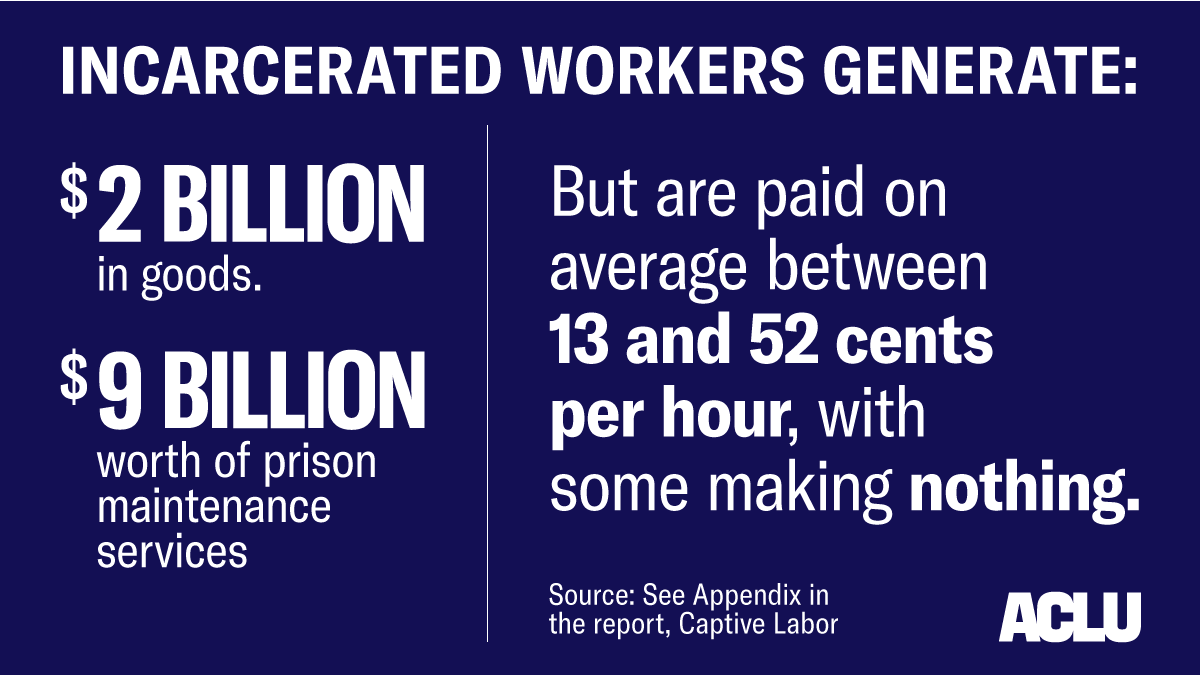

At the same time, incarcerated workers produce real value for prison systems and state governments, the system’s primary beneficiaries. Nationally, incarcerated workers produce more than $2 billion per year in goods and more than $9 billion per year in services for the maintenance of the prisons.

More than 80 percent of prison laborers do prison maintenance work, which offsets the costs of our bloated prison system. Many prison workers are assigned to general janitorial duties like sweeping or mopping, while others are assigned to grounds maintenance, food preparation, laundry, and other work to maintain the very prisons that confine them.

Another 8 percent of incarcerated workers, assigned to public works projects, maintain cemeteries, school grounds, and parks; do road work; construct buildings; clean government offices; clean up landfills and hazardous spills; undertake forestry work; and more. At least 30 states explicitly include incarcerated workers as a labor resource in their emergency operations plans for disasters and emergencies. Incarcerated firefighters also fight wildfires in at least 14 states.

State-owned businesses employ 6.5 percent of incarcerated workers and produce over $2 billion in goods and services sold to other state entities annually. Less than 1 percent of workers are assigned to work for private companies, which generally offer higher pay but are still subject to exorbitant wage deductions.

Prisons spend less than 1 percent of their budgets to pay wages to incarcerated workers, yet spend more than two-thirds of their budgets to pay prison staff. The revenues from commodities and services generated by imprisoned laborers prevent policy makers and the public from reckoning with the true fiscal costs of mass incarceration. Some government officials have even voiced opposition to efforts to reduce prison and jail populations precisely because it would reduce the incarcerated workforce.

Prison policy should not be driven by a desire for cheap labor. While prison labor is not a driving force behind mass incarceration in the United States, when incarcerated people are used for cheap labor, there is a risk that our criminal justice policy will be hijacked by the desire to grow or maintain this captive labor force.

A majority of incarcerated workers surveyed say that they received no formal job training, and many also say they worry about their safety while working. Incarcerated workers with minimal experience or training are often assigned hazardous work in unsafe conditions and without standard protective gear, leading to preventable injuries and deaths. Prisons don’t keep good records on the number of incarcerated workers injured on the job, but California reported more than 600 injuries in its state prison industry program over a four-year period. Because of poor data collection, this number likely underestimates the true impact of prison work on the health and safety of incarcerated workers.

Workplace safety and labor laws explicitly exempt prison laborers from the protections that virtually all other workers enjoy. Incarcerated people sometimes work in inherently dangerous conditions that would be closely regulated by health and safety regulations and inspectors if they were not incarcerated. Some are exposed to dangerous toxins on the job. In numerous cases we documented nationwide, injuries could have been prevented with proper training, machine guarding mechanisms, or personal protective equipment that would be standard in workplaces outside prisons.

Given the vast power disparity between incarcerated people and their employers, incarcerated workers are an exceptionally vulnerable labor force. These workers were especially vulnerable to exploitation during the COVID-19 pandemic. As most of the country stayed at home, incarcerated people faced brutal working conditions. Many reported being forced to continue working and were threatened with solitary confinement and having their parole dates pushed back if they refused to work. Workers in at least 40 states were forced to produce masks, hand sanitizer, and other personal protective equipment during early pandemic lockdowns as COVID-19 tore through prisons — even as they often lacked access to these protective tools themselves. Others were forced to launder bed sheets and gowns from hospitals treating COVID-19 patients, transport bodies, build coffins, and dig graves.

Nearly a third of incarcerated people have contracted COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, and more than 3,000 have died due to overcrowding, lack of access to virus mitigating tools like masks and vaccines, and inadequate access to health care. Yet even as COVID-19 turned prison sentences into death sentences due to COVID-19, 16 states denied incarcerated essential workers early access to vaccines.

Most prison workers surveyed by the Bureau of Justice Statistics — 70 percent — said the most important reason for working is to develop skills that they can use to build careers after release, but prison labor programs fail to provide incarcerated workers with transferable skills. In reality, the vast majority of work programs in prisons involve menial or repetitive tasks, and prison industries jobs and vocational training programs are declining nationwide, while maintenance jobs increasingly represent a larger share of work assignments.

Formerly incarcerated people are released with little money and face barriers to employment, including discrimination and state occupational licensing restrictions that bar people with conviction records from work in the very fields they trained in while incarcerated.

The majority of incarcerated people wish to be productive while in prison. They want, and often need, to earn money to send home to loved ones and pay for basic necessities while incarcerated. They want to acquire skills useful for employment after their release. Studies show that people who had some savings when they left prison and got jobs after their release were less likely to recidivate than those who did not.

Prison work that provides meaningful experience and skills, rather than pure punitive exploitation, is in all our best interest. Yet despite the potential for prison labor to facilitate rehabilitation, the existing system very often offers nothing beyond coercion and exploitation.

That needs to change.

We must push both state and federal lawmakers and prison authorities to eliminate laws and policies that punish incarcerated workers who are unable or unwilling to work. This will ensure that prison work is voluntary, and that people who refuse are not held in solitary or denied other benefits because they don’t want to — or can’t — work on behalf of the state.

We also need to guarantee incarcerated workers the same labor and wage protections as everyone else. This includes minimum wage, health and safety standards, the ability to unionize, protection from discrimination, and speedy access to redress when their rights are violated.

We must raise incarcerated workers’ wages and limit wage deductions. By paying incarcerated workers the state minimum wage, they will be able to pay for necessary expenses like child support, phone calls home, and commissary costs, while supporting their families and saving for eventual reentry into the society.

Prison workers deserve dignity. They should be properly trained for the work they perform, and we should be investing in programs that provide incarcerated workers with marketable skills that will help them find employment after release and eliminate barriers to employment and release.

Finally, we must push lawmakers to amend the U.S. Constitution to abolish the 13th Amendment exclusion that allows slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime. The 20 states with similar exclusion clauses in their constitutions should also repeal them. It’s past time to end slavery in all its forms — including in prisons.

You can read the full report below, as well as explore the stories of incarcerated workers here.